During the first year of the government of Iván Duque, one of the most sensitive issues on the national scene has been the permanent crime against human rights defenders and the country’s social leadership. The debate is marked by frequent questions such as: Who is behind the attacks, what are the causes and what is the Government doing. The responses from the State and government institutions are diverse and marked by places and measures as common as they are precarious: Increased resources for physical and material protection, awareness campaigns, militarization of territories and government programs to mitigate. However, none of those touches the underlying problem and, therefore, do not offer solutions to face the phenomenon, although it is as old as the violence itself in the country, it has developed into a very worrying situation.

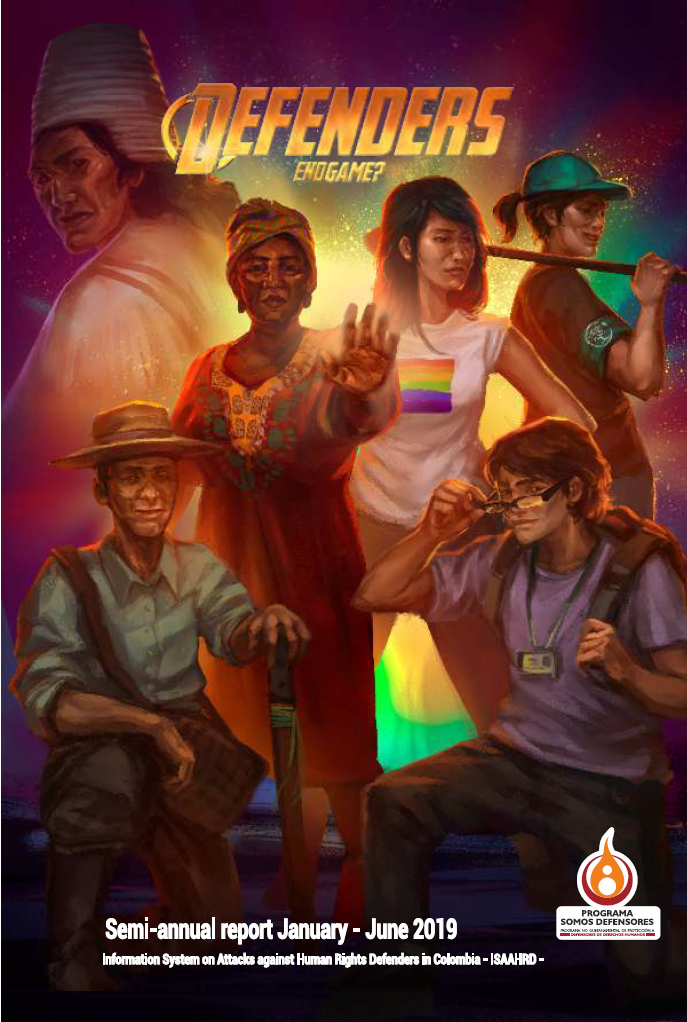

If at this time we compare Colombia to a movie, such could be Avengers: End game. This is because we are facing a State that seems to be under the power of Thanos, who only with a snap of his fingers tries to return us to the past and not let us out of the chaos, preventing the truth from being known, shutting up half of the country, closing the doors to democracy and emphasizing war and militarization, again. As is the case in the film, this is done to shape society according to the interests of a small group, overcoming collective needs and rights. Meanwhile, the human rights and peace defender society makes huge efforts not to lose what was achieved with the Peace Agreement and prevent new dynamics of violence from being installed in the territories and close once and for all, the armed conflict in the country.

Thus, this Report Defenders: End game? parodying the movie Avengers: End game, wanted to go beyond the media exercise, to investigate if the official approaches are reaching the bottom of the problem and if the proposed formulas respond to the challenge of overcoming the difficulty or if they continue to go around the branches without touching its root. However, this institutional reading is complex, to the extent that it is done in the midst of a context marked by government ambiguity between pretending to defend the Peace Agreement and deliberately ignoring it from actions directed openly against its very heart. Likewise, to attempt an analysis of the role and responsibility of the State in the critical situation of social leadership is even more complex, since it is necessary to distinguish between identifying the role of senior officials who have a genuine vocation to find solutions to the problem, and those that in their role of power place it at the center for their political profitability.

The report is divided into four chapters. In the first chapter, One Snap and It’s Over, some of the actions are exposed, actions that this Government has carried out to try and erase with a single blow what others have tried to build with a huge effort, such as the alternative of a different country, and those that it has used to create from the speech of its own version of reality, above the difficult situations that hundreds of communities in the territories are evidently going through. The denial of the armed conflict and the disregard of important provisions of the Peace Agreement between the Government and the demobilized guerrilla of the FARC, are a sample of what is meant to be erased with a single snap, regardless that this could destroy the possibility of overcoming an important part of our conflicts.

The second chapter, The Order Through Chaos, shows how in addition to the fact that key elements of the reality of the country are being ignored, a particular “order” is being imposed by the Government, shaped through its interests, but which is cemented in chaos and, particularly, in the return to measures from the past that were the flag of previous governments. Thus, issues such as the militaristic approach, extrajudicial executions and the old democratic security camouflaged under new names, appear. These actions of the Government plus the reconfiguration of violence and armed conflict in the territories, leave the feeling that we’re returning in time and that little by little chaos is imposed, which destroys all the efforts made by society in recent years in the defense of life and peace.

The third chapter, Defenders: Infinite Force, is a recognition of the indestructible strength of human rights defenders, who despite being in the midst of fear and aggressions, do not stop working for collective rights, even risking their own lives in the process. These struggles have been increasingly evident and they have been joined by various sectors such as politicians, media, international community, organizations and the same society, which have been mobilized permanently and massively during the first semester to condemn the systematic attack of human rights defenders and to demand guarantees to protect their lives.

In the last chapter of the Report, the data analysis of the Information System on Aggressions against Human Rights Defenders in Colombia –SIADDHH–, which is based on the cases registered and verified by the Somos Defensores Program, is presented. This time, the results show that at the end of the first half of 2019, a decrease in the statistics of murders against social leaders was evident, which decreased by 23% compared to the first half of 2018; nevertheless, and very unfortunately, violence against these activists, in general, is maintained and has increased; due to strategy changes in in the territories, it is mainly reflected in other types of non-lethal aggressions, such as threats.

In addition, due to the strength that the conflict has achieved in the regions and the electoral landscape, it is feared that the trend will not be maintained and that the figures may increase at the end of 2019, especially those of murders.

Finally, we would like to extend our thanks to all the people and organizations that surround the work we do at SIADDHH, especially to the Center for Popular Research and Education –CINEP–, to the Colombia Europe United States Coordination –CCEEU–, to the Indigenous Organization of Colombia –ONIC–, the Office of the Ombudsman and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Colombia –OACNUDH–. In addition, we want to acknowledge the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Colombia for its constant political and financial support, and the international cooperation agencies DIAKONIA Sweden, MISEREOR Germany, International Amnesty and Pan Para el Mundo (Bread for the World). Their support is essential for our work and for the preparation of this report.